THE CHANGE

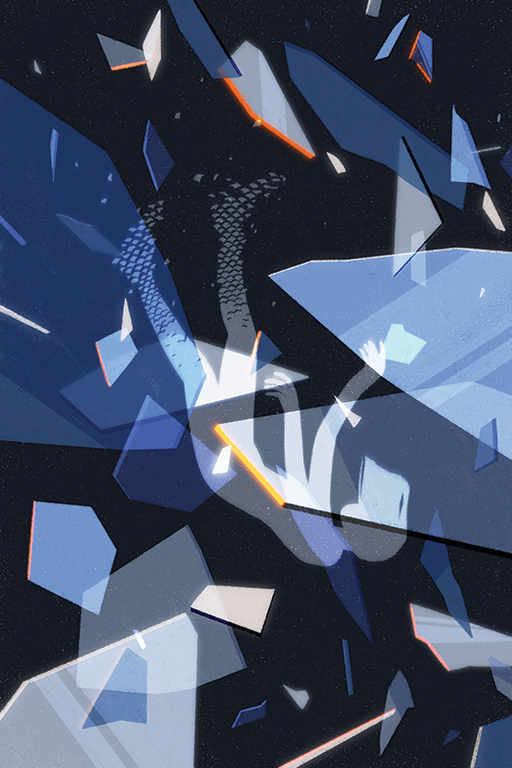

This incisively witty short story by Rowena Fishwick examines mermaids, puberty, girlhood and motherhood. Illustration by Ran Zheng

It started a little before my fourteenth birthday. The day was hot and I lay in the shade, close to the river, sweating as I turned the pages of a steamy paperback. Aches throbbed like tiny punctures up my back and thighs. Every so often those aches burst into pain. When that happened I screwed my eyes shut. The black words burned in my head, transforming into insects that crawled around and around until I was sick and dizzy.

“You’re meant to be playing with me,” Hannah said, and I groaned. She’d found my hiding place again. “You can’t just laze around reading all summer.”

The pain passed. I rolled onto my side.

“I can if I want to. Besides, I’m too old for all that.”

“You’re mean.”

“And you’re a numbskull.”

“You’re not to use curse words. I’ll tell.”

“Numbskull isn’t swearing.” I shifted my hips, trying to get comfortable. Then the aches exploded. I cried out. “Shit in hell.”

“That was a bad word.”

I rolled onto my front. “Not as bad as –“ Pain raked my thighs. “– Jesus fuck.”

I sucked in my breath. My fingernails clawed the grass. I tried to look at Hannah, but she was a fog of orange hair and green cotton.

I curled myself up, panting. Perhaps if I made myself smaller the pain would also shrink. But it didn’t.

“What’s wrong with you?” Hannah asked, warily, as if this was a practical joke.

“You stupid little bitch.” I spat the words onto the grass. “Just get away. Or I’ll… I’ll…” I howled.

When I looked again, Hannah had gone. I couldn’t care. Pain trumped everything.

My hand brushed my leg, where the burning was worst. I felt something hard and cold. Gradually, I managed to turn my head and peer down. That’s when I saw the scales. They’d broken out all down my legs. Shimmery green scales that rippled when I moved. I scratched one of them, picking until I felt blood. Then my lower body began to convulse. I was being ripped open. Ragged screams tore from my throat. They must have taken my last trace of energy, because I blacked out with them still ringing in my ears.

*

“Lydia?”

I opened my eyes. My shade had been carried away, so I lay right in the glare of the hot, bright sun.

“Lydia.”

“What?”

“You need to be in the water,” Hannah said.

I tried to speak again, but I was parched. Like a dried up snake skin, crackling into dust. But at least the pain had stopped.

“Come on.”

Hannah stooped and jammed her hands under my armpits. I shifted away. Or tried to. Something was wrong with my legs. I looked down and saw the tail. Startled, I tried to get away from it, but the tail moved with me. That’s when I realised. It was my tail and it reached all the way up to my belly button.

“We need to get you in the river.”

I gaped at her. Wasn’t she fazed that I was now a mermaid?

She tried to drag me towards the water. Her mouth puffed air on my face. Sweat glued her hair. But it wasn’t working.

“You’re too heavy,” she said.

“I’m not fat. It’s all tail.”

Somehow, between us, I made it to the bank. The grass was cooler there. Moisture soaked into my pores. I imagined those pores like grasping mouths sucking at the water, desperate for every last particle. Hannah shoved me, rather abruptly, and I rolled into the water.

The river greeted me with a hard smack.

*

“What’s it like?” Hannah asked. She was sitting cross-legged on the grass, making a daisy chain. There was something picturesque about her, like a child in a Victorian painting. I, on the other hand, looked like an entirely different kind of painting.

“Can you talk underwater?”

“No.” I turned the page of my book, not because I was reading but because maybe she’d think I was and shut-up. Hours had passed and her enthusiasm grated. I lay sprawled on the bank, my elbows propped in the dirt, my tail frolicking on the water.

“How do you…you know… go to the toilet?”

“Through my mouth. Not everyone talks shit metaphorically, you know.”

“Gross.”

“You think I have all the answers? You think I turn into a mermaid and suddenly know how it all works?”

“It’s all rather…” She gazed at my tail, her eyes getting misty. “Magical.”

“You mean fucked up.”

“I’ll tell about that one.”

I laughed.

“You think she’ll care about my language? Look at me. I’m a fucking mermaid.”

Hannah slipped the daisy chain onto her head. Wilted petals landed in her tangled hair. “We have to tell her.”

“Are you mad?” I said. “When Dad married Mum she was so scandalised she didn’t speak for over a month. And that was only because she was Eastern European. The shock of this would probably give her a heart attack.”

My lips twisted into a smile.

“On second thoughts. You’re right. Go fetch her.”

Hannah brushed the remaining daisy heads off her lap and hurried up the lawn, towards our house. When she was gone I tossed my book aside.

Something moved on the water and I froze. Boats rarely went past, except on their way to the annual regatta, and that wasn’t for another week. In the past we’d picnicked on the grass and watched them go by. Mum would sunbathe in a black playsuit, cut so low that when she rolled over it flashed her nipple. But this afternoon there was no boat.

The movement was my own tail, writhing like a serpent on the water.

*

Grandma strode up the lawn towards me. Her skirt clung to the opaque stockings she always wore, no matter how hot it became. She was a plain woman. Meaning there was an absence about her, both of beauty and ugliness. She was born the year Queen Victoria died, which made her almost sixty that summer, but she looked a solid fifty. Photographs of her as a child revealed she’d always looked a solid fifty.

As she came closer, my smile faded, because Grandma wasn’t shocked. She gave my tail a moue of disdain, the same as when she’d caught me smoking. I half-expected her to blame this, as she had that, on my watching too many American pictures.

“So,“ she said. “It’s happened. The change.”

“It’s hardly like I’ve got my period.”

Her eyes hardened. “Period is a common word.”

I laughed and my tail twitched.

“She said it would.”

“Who?”

“Your mother.”

“She knew about…this?”

Grandma looked down at me. “Of course. She was one, too.”

I shuffled, wanting to stand because I was the same height as her now, and could meet her gaze. But, of course, that was when I had legs.

“That’s a lie. She was human.”

“Sometimes. Then, once a month, this happened.”

“So this isn’t permanent?”

My body was baked and I longed to go back in the water. My eyes turned to the river, as if they could feel it watching me, calling to me.

“I expect it will last a few days.”

“Did Dad know?”

She snorted. “One advantage to him being in the army, he was home so seldom we could hide it from him. As we’ll be able to hide this. Your poor father had no idea. He thought she was some kind of goddess. Ever since he found her living by the Danube River after the war. Wouldn’t hear a word against her. But I knew. The first time I saw her, I knew she was trouble. Of course it wasn’t until you came that I realised what sort of trouble.”

Memories of Mum flickered across my mind. Her ink-black hair, those intense eyes, and her laugh. She was always laughing. For a while, after she left, I’d hear that laughter in the house and search for her. As if she was playing another game of hide-and-seek and I’d discover her crouched in a wardrobe or under the stairs. It took a long time to accept the house was empty and the laughter was only a memory.

“I was with her when you were born. I saw your tail.”

“I was born with a tail?”

“She said all you lot have tails in the womb, only it’s usually gone by the time you’re born. You were a month early, so it hadn’t… Anyway, she told me everything then. About herself and the curse. And what would happen to you.”

“And you never thought to tell me?”

“Would you have believed me?”

I glared at the river. “What about Hannah?”

“She didn’t have a tail. Of course she wasn’t premature. We’ll have to wait and see, but she’s always favoured your father. I have hopes she’ll be normal.”

Normal. The word resounded in my head. I would never be normal. That was when it truly hit me. I was a mermaid. An actual fucking mermaid.

“What happened to Mum?“ I asked. “Where did she go?”

“I don’t know. She just up and left. It was the only decent thing she ever did. We’re all better off without her.” She straightened her back. “No-one can ever find out about this. You understand?”

I nodded. I understood all too well. Her mouth twitched at the corners. Not a smile. Grandma never smiled. The only one on record happened when Mrs Thompson’s roses were ruined by aphids, and she lost her reigning championship at the annual flower show. There was certainly no smile now. She turned and walked away, and I watched her getting smaller and smaller. Except it felt like I was the one who was shrinking. Disappearing into this new body. And there was a loneliness so staggering that, for a moment, I couldn’t breathe.

*

A year passed. A year that was a fog of changing, waiting to change, and trying to block out the knowledge I would change with alcohol and parties.

“You’ve become someone else,” Hannah said to me.

“Give the girl a round of applause. Course I’m not myself. I’m a fucking mermaid a quarter of the time.”

“It doesn’t mean you can’t act like a lady.”

“Oh, fuck off.”

Hannah had stopped flinching at my language. At most she’d give me a withering glance. It was worse when the change was due. Along with the aches came an uncontrollable rage. She’d learnt to keep away from me then, after the time I threw her copy of Anderson’s Fairy Tales at her head because I’d caught her reading ‘The Sodding Little Mermaid’ for the fifteenth time.

At least the rage gave me a clue the change was coming. It was worse when it arrived unexpectedly, as it did one summer evening.

I was partying by the river with a group of boys. So wasted I didn’t notice the jerks starting in my body. It was only when I began to convulse that I knew I had to get away. Somehow I made it under the shadow of some trees. They must have heard my screams, but by that time I was too lost in the change to care.

It was morning when I came around. I must have got inside the river before I blacked out, because its water surrounded my body. A flurry of fish charged towards me, some slapping my arms as they hurried off into the murk. Something was happening. Vibrations pulsed through the ground. But I was still drunk and the change had exhausted me. I couldn’t find the energy to move.

A boat passed overhead, blocking out the sun. Waves followed it, rocking me so my arms scraped grit. Then there was another boat. And another. I remembered: the regatta. I had to get away.

But something was tugging my head. I reached to prise it away, but it wouldn’t budge. It got harder, firmer. I looked up at my long, billowing hair, and realised what had happened. It was caught in a propeller.

Everything became panic. Bubbles billowed around me as I tried to yank myself free. My hair was winding tighter, tighter, and I was dragged closer and closer to those blades. The boat gave a stutter. The propeller stopped. Then, with a kick, it started again, harder than before, and I closed my eyes knowing what would happen to me.

Then my hair was loose. Something – someone – was in the water with me. The boat moved away, pieces of my hair trailing behind. I reached up and felt where it had been cut from my skull. Then I looked at the woman beside me. And her tail.

We swam to a quiet part of the river.

“You look different,” I said, when we broke the surface.

She laughed. Then said something in a language I didn’t understand. The words tangled one on top of the other.

“Sorry,” she said. “I haven’t been in England for a long time. I was saying that you look different, too.”

“Where have you been?”

I watched her smooth down her hair. She was still beautiful. Her naked breasts bobbed on the water and her skin had a silverfish glow.

“I came back when I thought you’d need me.”

“Well, you’re a year too late.”

“A year? So this isn’t your first change? Ah, well I’m sorry.”

“You don’t sound very sorry.”

She sighed. “Well, I couldn’t have known you’d be an early developer. I didn’t have my first change until I was fifteen.”

She sounded so blasé I wanted to scream at her. Tell her about the torment of the past year. The time I tried to slice my tail off with a kitchen knife, when I started to change at school and barely made it to our street before my tail sprouted, and the times I let boys fuck me just to prove to myself I was still human.

“Didn’t you think of coming back for any other reason?”

“What else would you need me for?”

“You’re my mother. How could you leave?”

“I’m a wanderer. A free spirit. I told your dad this when we married, but he thought I’d change.” She picked at a cuticle. “Do you have to interrogate me, Lydia? You sound just like that old crone. I’m beginning to wonder why I came back. Although it’s clear you’re making a mess of this whole thing. Drinking when the change is due. Have you no sense?”

“I apologise.”

She didn’t hear the sarcasm, or chose not to. “We have a reputation to uphold. Mermaids are meant to be beautiful, enigmatic. Not drunk and bedraggled. You need to be more like me, Lydia.”

“You think I want to be like you?”

“Well,“ she blinked at me, her eyes puzzled. ”You are.”

“So you’re going to stay?”

“Of course not. You’re coming with me.”

“What about Hannah?”

“She isn’t a mermaid. At least not yet.”

“Don’t you even want to see her?”

“Why?”

“Have you always been this fucking selfish?”

She thought about the question.

After a while she said: “I suppose so. Now, are you coming?”

I stared at her. She grew bored and let her eyes drift around. Water lapped against her breasts, sunlight poured over her flawless skin. She reminded me of a fortune-teller I’d once seen at the carnival. Reading a bad fortune with as much emotion as she might read a shopping-list. My thoughts turned to Hannah, and how different things could have been if someone had prepared me for all this.

“No,” I said. “I have to stay.”

“Very well.”

“But you’ll come back?”

She tossed her head.

“I don’t see why. But, if you wish, I’ll try to sometime. Just remember to stay away from drink. Oh, and jellyfish. I know that from experience.”

Then she ducked under the water and swam away.

A few days later I changed back. It was evening and starlight sprinkled the black sky. Hannah always left me dry clothes by the bank and this time it was a peculiar concoction that made me look like Peter Pan.

The house was quiet, but a light flickered in the living-room where Grandma was watching TV. And I wondered if she’d been sitting up for me. If she worried about me during my absences.

“So you’re back,” she said and turned to look at me. “You’ve seen her, then?”

I knew who she meant.

“Yes.” Grandma snorted.

“And how was she?”

“She was…” What could I say? Selfish? Charming? Thoughtless? Beautiful?

She gave a dry laugh, as if she’d read my thoughts.

“She always was.”

I left her there and went up to the bedroom I shared with Hannah. She was asleep, moonlight touching her freckled face. Her Anderson’s Fairy Tales was face down on the table and, turning it over, I saw it displayed ‘The Little Mermaid.’ She stirred and her eyes blearily opened.

“You know this isn’t a fairy-tale,” I said.

“Then what is it?” she asked, her voice croaky. “What’s it like? You never tell me.”

“It’s…” Her eyes watched me, waiting. How could I begin to explain? It was pain, it was fear, it was loneliness. Yet, in the past few days, it had become something else as well. It was the power of breathing underwater. It was moments of pure freedom. Freedom from the constraints of being human, being a girl, being young. It was… I slammed the book shut.

“Fucked up,” I said, and smiled.

This story featured in The Fantasy Issue of Popshot Quarterly.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.