THE SHORTEST DAY

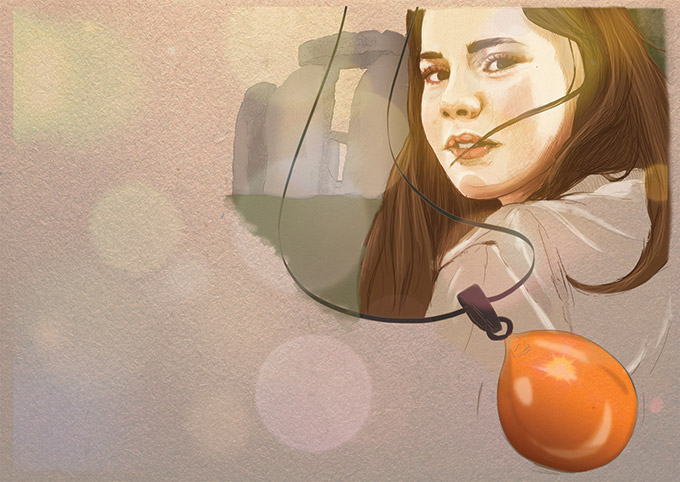

Andrew Hanson’s short story explores the significance of the tales we tell ourselves about our past. Illustration by Burcin Pervin.

‘Oh. I thought I might be,’ said Kerry.

‘That you might be adopted? But, how?’ Cassie’s face went moon-shaped.

‘Well I don’t look much like you, do I? And I’m not clever enough to be Dad’s.’ She twisted a lip piercing. There was silence, save for the sparrows cheeping outside.

‘It doesn’t make any difference. We still love you,’ said Cassie.

‘We love you just the same, Kerry,’ said David.

‘Yeah, you keep saying.’ Kerry stood and wandered over to the cat basket, but the cat evaded her grasp and trotted away.

‘Come here,’ Cassie said, her arms spread out. ‘Look, you’ll always be our little girl.’ Kerry stumbled to the sofa like a spent athlete. ‘So for fifteen years you’ve been lying to me,’ she mumbled, her chin dug into Cassie’s shoulder. ‘No, no, we are still your Mum and Dad. It’s just –’ ‘It’s just biology,’ said David. ‘Just a detail.’

‘I knew I didn’t fit in here.’

‘Of course you do Kerry, you belong with us,’ Cassie replied, her eyes fixed on the serene, blue-robed Madonna and child above the mantelpiece.

‘Don’t lie. And stop looking at that bloody picture. That’s another story, same as the story you’ve just told me. Everything is a story.’

‘No Kerry, what we told you is true. And that picture is true, too.’

‘We understand that this is a lot for you to take in,’ intervened David.

‘It’s OK, Dad. I get it, it’s cool.’

‘We have two things to give you, Kerry,’ said David, reaching for a shoebox in a plastic bag. ‘Things from your birth mother.’

‘Okay,’ said Kerry, unable to muster any other response. She slipped from Cassie’s lap and sat on the floor, eyes wet, lip twitching. David produced a small jewellery box and handed it to her. Inside was a large, misshapen amber bead hanging on a black cord, unusual but not ashy.

‘And there’s this,’ he said. Unwrapping tissue paper, he handed Kerry a small embroidery sampler. ‘Your birth mother wanted you to have it, but we don’t know why. It’s just something she made.’

The sampler was white, with a simple flower border surrounding neat letters and a sun and moon in the bottom right corner. ‘On the shortest day, the highest light will lead you from under the bridge. Matthew 11:13-14,’ read the text.

‘It’s a cheerful message,’ said Cassie defiantly, through her sobs.

‘Yes Mum, it is,’ said Kerry, feeling stronger when faced with her mother’s distress. That evening she borrowed Cassie’s Bible, and looked up the reference. ‘For all the prophets and the law have prophesied until John. And if you are willing to receive it, he is Elijah who was to come.’

So the embroidery text was make-believe; a fake, rather like she was.

*

Kerry passed the next few days waiting for something final to happen, like a prisoner writing on the wall of their cell who is about to run out of space. Somebody would say, ‘That’s enough,’ and she would freeze. Her charade of a life would be over. Yet time went on, absurdly enough. She was walking out of school one afternoon, when scanning the crowd ahead of her for a friend, she caught sight of a woman waiting by the traffic light barrier on the other side of the road, a woman gripping the steel rail with both hands, head slowly turning, eyes searching nervously. A woman of about forty, with strong features and a ruddy complexion, dark hair tied back. Kerry made eye contact across the congealed school-run traffic, and something happened; a transfer of energy. A van passed, she looked briefly away, and when she looked back, the woman was gone. Her first thought was to dismiss the episode. Yet there had been a resemblance, and there had been a feeling, a real feeling.

*

Sitting in the kitchen that evening, she was untangling her earphones while her mother made dinner.

‘Cass, –’

‘Call me Mum, please Kerry. I’ve brought you up, after all.’

‘I should have clocked it sooner, shouldn’t I? I mean, you’ve got red hair.’

‘It’s best if you don’t think about it. We both love you, and that’s all that matters.’ Fat sizzled in the grill as she turned a pork chop over.

‘After school today, I saw this woman waiting. She was looking for someone, and I thought –’

‘Oh Kerry, you mustn’t. You’ll hurt yourself, thinking like that.’

‘But I don’t know anything about her, about the woman who gave me up.’

‘All we have are the necklace and the embroidery. That’s it.’

‘Do you know her name?’ There was silence. ‘So you do know her name?’

Cassie pulled a chair out and sat down, clasping her hands.

‘We can’t tell you until you’re older. This won’t do any good, Kerry, please. She’s been gone from your life for a very long time, and she isn’t coming back. Your life is with us.’ Cassie reached out until Kerry took her hand limply. They sat there for some time, glancing at each other, like a light flickering on a weak contact, until the fat in the grill pan started to burn, and the smoke alarm sounded.

*

Researching the shortest day and highest light led her to the Wheel of the Year, druids, Stonehenge, and a whole load of mystic crap. Solstices and wonky geometry, stones that were very old and people who were barely sane. She read about the verses from Matthew that mentioned Elijah, which turned out to be about reincarnation, or a second coming of some sort. All of them magic stories, whether pagan or Christian, all of them lame and unhelpful. Stymied, she put on her headphones and cocooned herself in noise. Nothing was real, least of all her distress. She was watching herself from a long way away. She wished somebody else was, too.

*

Late on Friday evening and David was liquid with fatigue, undone by work stress and red wine, pooled in the middle of the sofa. Kerry leant against him and folded her head onto his shoulder.

‘What do you think it means, Dad? That piece of embroidery?’

‘I don’t know, Kerry. Really.’

‘But you’re a doctor. You know what people are like. I reckon you’d have some idea.’

‘People like their sayings. The darkest moment is just before dawn, that kind of thing.’ ‘Then why say it was from the Bible when it isn’t?’

‘Maybe she wanted to give it some gravitas, some weight. Maybe she wasn’t very well.’

‘Why do you say that?’

David pulled away and stood up, stretching.

‘Too many questions for a tired old boy like me, Kerry. I should join your mother –’

‘Is she still alive?’

David stopped, then bent down to kiss Kerry on the forehead, but she put a hand on his chest. ‘I have to know, Dad. It’s torture, it’s wrong, you can’t just give me part of it, you can’t!’

‘Not now Kerry, please.’

‘Is she still alive?’

He squatted on his haunches, knees cracking, his face pained. ‘She died, Kerry. After she gave you up for adoption. We weren’t going to tell you, but it seems better that you know. I’m so sorry.’

Kerry tried to obliterate him with a hug, choking down sobs as she squeezed.

*

After that, she hadn’t been able to ask any more questions. Survival dictated silence. The colour of a sunny October was rinsed out by November deluges, until towards the end of the month a cold grey stasis descended on Somerset, England, perhaps the world. At the beginning of December, the three of them went for a walk. They passed a view of Glastonbury Tor, then left the ridge and descended towards a pub in Wookey Hole. A few fields later they came across two craggy monoliths in a field.

‘Oh, look, Kerry, standing stones!’ said Cassie. ‘Probably really old, prehistoric.’ ‘Why would anyone leave stones like that in a field?’

‘Possibly boundary markers,’ David replied. ‘Or they may have had a ritual use. Perhaps people gathered around them, lit a fire and danced. A sort of prehistoric festival.’

‘Or maybe they were there to throw shadows, or catch the light at a special time of year,’ Kerry said.

‘Well, yes, quite possibly…I didn’t think you were interested.’

‘I’m not. It’s a pile of crap. Like the embroidery that my mother left me.’

‘Oh Kerry, not now!’

Kerry walked ahead, then turned to face them, ripping out her earphones.

‘What was her name? Just tell me her name and I’ll leave it.’

‘Kerry…’

‘It’s like, there’s this gap inside my head.’

A taut glance between the two adults followed, eyes flexing.

‘Her name was Mary O’Keefe,’ said David, voice deepening.

‘Mary O’Keefe? Right, shall we get to the pub then?’

‘It’s probably an Irish name,’ said Cassie, but Kerry was already striding downhill.

It was, of all things, a history lesson a few days later that spurred her on. Propaganda and Stalin. ‘He who controls the past controls the present, and he who controls the present controls the future,’ her teacher quoted. Her own past was still full of small round spaces, blisters on her brain filled with clear water, empty speech bubbles in the cartoon of her life. Cassie and David would tell her no more, and the message on the embroidery remained unpicked. Questions at school, a pretence of family research, internet cafes and learning about death certificates followed. Then coroners’ inquests and the intrigued acquiescence of an eighteen-year-old friend on a trip to the Coroners Office.

It took them a while to be taken seriously. Eventually, the clerk took them through and they found the appropriate year — commencing just a few weeks after Kerry’s birth — and began checking the index. Nothing. Too early, perhaps. The index for the year after yielded no results, and the year after that. Despite disapproving glances, Kerry was determined to continue, even though she knew that the absence of a name did not mean her mother was still living. When she did find the name, Mary O’Keefe, all the other letters on the page dissolved. The report was mercifully short: verdict of suicide. She had thrown herself off a bridge on the River Sheppey twelve months after Kerry was born. Her friend scanned the details. No body was ever found, hence the delay, no contact with her surviving parent, and the coroner made a Presumption of Death Order. They got a photocopy and Kerry wobbled out before she disintegrated entirely.

*

The shortest day was breezy with broken sunshine, the kind of December day where weather blows through so fast you think that winter might only last a couple of weeks. Kerry made the journey on her own, feeling cold, windswept and barely connected to her own body, let alone the dead spirit of someone else. The amber bead hung on its cord around the roll-neck of her jumper. She came to a humpback road bridge. The underside was red Victorian brickwork crazed with spiders’ webs, the air dank and there were muddy puddles underfoot. As she looked around, it suddenly hit her that she had been expecting something vaguely transcendent. The wind coaxed tears from her eyes. This probably wasn’t the right bridge. Her location on the map was uncertain, based on guesswork and chance. She was virtually lost.

She walked up onto the road and managed a few paces in no direction in particular. A beaten-up Volvo turned out of a farm driveway and pulled up beside her, the driver winding down the window.

‘Are you alright?’ said the woman. There was something familiar about her face; a strong nose, nervous eyes and a firm expression.

‘Er, yeah, I’m trying to find a bridge on the river.’

‘Which bridge might that be?’ The woman turned the engine off and got out of the car.

‘It’s called Swanshard bridge.’ Kerry pulled the map close to her chest. ‘It’s for a school geography project.’

‘You want the next one going west, my duck. That way.’ Her eyes rested on the amber bead and she nodded. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Kerry Williams, not that it’s –’ The woman was getting back into her car. ‘Hey, wait, who are you?’

‘Debbie Maynard. I have a daughter at your school.’

‘So you’re not…?’

The woman’s lips pursed with regret, wrung out like a cloth. ‘You shouldn’t go there… just go home, love,’ she said, and shut the car door.

‘I thought you were looking for me, that day after college…’ said Kerry softly, drowned out by car tyres chewing the gravel.

She picked her way between puddles, oblivious to the acid green of the winter grass or the rippling of the swollen river as it coursed westwards. Her pace increased as her thoughts gained momentum. Something was nagging her about the brief exchange. As she cast her mind back, she recalled there was a witness in the inquest notes — a Deborah or Debbie. She said she had seen her mother jump from the bridge. Kerry’s face flushed, her fingers and toes fizzed with blood: it seemed she was owed no explanation, no kindness beyond a sad smile, and nothing solid to cling on to.

The bridge was a road bridge, low and squat, concrete underneath, surprisingly broad, with a sign forbidding fishing and little else. The river narrowed here, the water swirling with cold ebullience, black and opaque as jet. It would claim anyone who offered themselves. Kerry checked her watch. Midday approached, though there was no sun.

Just after twelve, the clouds parted. The river was owing directly north here, that much was clear, for the bridge captured the southern sun like a golden bolt sliding through a stone recess. The light was low enough to pass underneath the road above, parallel to the concrete walls, raising a surface that had been paper-smooth to a rough, grainy consistency. Every scratch and imperfection were visible. And there, just below the roof, engraved in rough capitals, a simple message.

Kerry, I will meet you at Avebury rings at dusk tomorrow.

The letters were faintly highlighted by green mould. They had clearly been there for years. And if tomorrow ever came… then her mother was alive. Her heart was a rising drumbeat and she put her hand out to steady herself, the concrete electric beneath her fingertips.

*

A day later, Kerry was cycling into a vicious south-westerly wind, her face freezing as she pedalled out the miles from Swindon station. Sleep deprived and hungry, she had no idea what to expect, apart from some rings of standing stones.

Despite having seen photographs online, the site was larger than she had expected. A wide, at, green place, the cluster of houses and trees in the centre making it impossible to gain a clear view of the whole. She walked around the perimeter of the outer ring, watching the sheep grazing in the deep ditch to her left, and listened to the jackdaws. The stones were enormous. Rough, untamed and mottled by lichen, they demanded to be touched, and Kerry could not walk past one of them without reaching out and feeling the surface abrade the skin on her fingers. A person could hide behind even the smallest of them. At the next stone she turned her palm over, scratched her black nail varnish, grazed her hand and winced. She had no idea who she was looking for, or where to find them. She turned, waited, and turned again. No one was coming, there was no certainty her mother was alive. Nothing made sense. Even this place, with its jagged claim to timelessness, was a story of sorts. She had read that half the stones had been re-erected by a man who had made a fortune selling the Victorians marmalade. It might be prehistoric, but it was still junk. She wandered around and away, looking for a café, somewhere to get warm, though she couldn’t face the National Trust tearoom. A nearby pub would be better.

She bought herself a pint with fake ID and sat by the fire. If only she could remember everything, back to the instant of her birth. Even the memories she had retained were hollowed-out, watery projections on a flimsy screen. See-through and shifting like flames. She sat there, barely moving, for two hours.

As the day began to fade, her fingers played with the misshapen amber bead, rolling it around the black cord, learning its contours by touch. It seemed to swallow the light from the re and glow with a deeper radiance of its own. All time had tapered to this point, this moment, this now. She left the pub and walked outside, the chill hitting her face like frozen gravel. The rings were deserted, the stones ugly sentinels on a round perimeter, crooked teeth gouging a blazing sunset. The wind ruffled the grass and shook crows cawing from the trees. Kerry turned and walked into the sun, trying to capture some last particle of warmth. She passed the final stone and waited, her eyes now saturated with light. Somebody moved behind her, walked by her shoulder, stood, and was staring at her. Kerry’s eyes broke from the sun and tried to guess at the human shape to her side, but for a few seconds all she could see was shadow.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.