TRUE ABNORMALITY

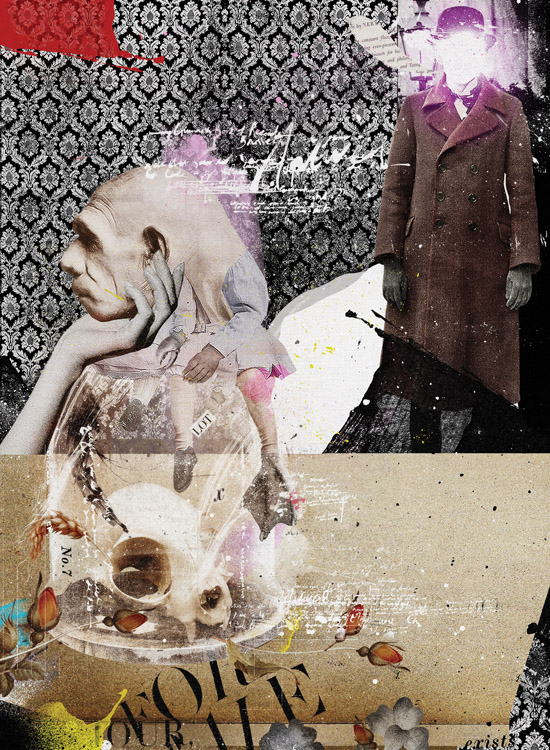

A deceitful creator of strange creatures finds his scepticism challenged in Alys Hobbs’ curious short story. Illustration by Phil Couzens.

Ralph was in the workshop late, winding gauze around wire, his fingers gummed together with glue and tufts of hair. The lamp flickered. In the empty apartment upstairs a grandfather clock counted the minutes. Other than that, all was quiet. No carriages on the road outside. No voices on the street. No one else awake in the world, it seemed, but Ralph himself.

He bent low over the table, his hands darting, stitching, moulding. Every now and again, he bit off a stitch or changed his brush. A glass jar, mottled and stained, sat on the bench beside him, awaiting its inhabitant. This was going to be a good one; a two-headed rat with little human hands and a lecherous mouth. A thing of true evil, Ralph would say. As he worked, he practised the patter under his breath, his lips twitching, his eyes reddening and stinging as the hour slid by.

Discovered in the catacombs of Paris, he would mutter in a quivering voice. Smuggled over on a ship just last week. I hear many of the crew came down ill on the voyage, complaining of terrible dreams. The captain hasn’t been seen since they docked…then he’d look around anxiously, maybe dabbing at his forehead as though he were fighting a fever himself. It’s a strange one, this, and I’ll be glad to be rid of it.

And then they would barter a little, he and the fairground owner, or the barman at the Blind Tiger, or Mrs Beet at the curiosity shop — whoever he decided might give him the better deal. He would sweat and tremble and shake his head until they reached a price that pleased him; and then he’d hand it over, slowly, almost regretfully. And of course they would take it, his twisted, sneering little forgery. They’d take it though part of them knew all too well that it was a shill. They’d take it because the wondering child gaping out from behind their eyes wanted it to be true, needed there to be such things as the strange nightmares he sold. Because, if such things were real, what else might there be? Angels, perhaps, or glittering life beyond the void?

They would place it on a high shelf or in a window, make it the star of a new exhibition, and people would come from all around to see it, to feel their flesh crawl and their hearts flutter in horrified delight.

Meanwhile, Ralph would be kicking his feet up somewhere with a fine bottle of whiskey and a hearty meal, living a life of relative luxury and grinning himself to sleep — for a week or two, at least, until the money ran out. Then, it would be back to the workshop, to the wires and glue, the boxes of hair, the scraps of fur and the glass eyeballs, the bottles of teeth he’d picked from stray cat skulls and trapped mice, and all the other trims and trappings that made up the ghastly parade.

Ralph was not an honest man, but he saw himself as an entertainer of sorts. And if so many fools wanted to spend their money gaping at mutated rodents and skulls with too many eye-sockets and six-fingered monkey paws, he would surely meet the demand. There was always someone who would buy. Sometimes big collectors and business owners like Mrs Beet, who used the curiosities to drum up customers. And some strange types, too, who would pay in clammy handfuls of odd currency and gaze at their purchase with hunger. Ralph did not care much for their sort, but as long as they kept him in bed and board, he wasn’t exactly going to turn them away.

Besides, he had worked hard to build himself a solid reputation in town. ‘A Specialist Collector of all Things Supernatural’ his calling card read. He made sure to maintain an air of mystery about his person, never giving away where he came from or where he lived, and making sure that he was often seen scuttling about clutching old books and misshapen tools with apparent purpose. These things just seem to seek me out, he would say with a shrug. It’s as though they’re drawn to me, and I to them, like we’re supposed to find each other. It’s always been the way, ever since I was a boy…

His listeners would widen their eyes, and speak in hushed tones, saying how strange, how bizarre, how exciting. They would gape at him, and then at whichever monstrosity he had built, regarding it with trepidation and barely-disguised lust. Then they would pay up, and Ralph would have to bite his knuckles to stop from howling with laughter as they left.

The grandfather clock chimed in the apartment above, disturbing him from his work. Midnight, it sang, and Ralph sat staring ahead as the peals rung into the quiet. A light rain speckled the window. The lamp flickered. He rubbed his eyes, stretched his back until the joints popped and cracked, and thought about his bed.

Suddenly, there was a knock at the door.

Ralph sat for a long moment, listening. His mind occasionally played tricks on him when he worked so late. He often thought he heard such things as little nails scratching, or tails slithering, or snatches of whispered conversation. Sometimes, he even thought he sensed movement behind him, but when he turned around all was still. The usual troubles of a tired man who sat up late into the night.

But there came the knock again. A quick, insistent knock, muffled as though the knocker were wearing gloves. Ralph got up slowly. He crossed the room, glancing out of the window as he went to unlatch the door. The glass was thick and warped, but he could see that there was someone out there in the rain, their silhouette framed by the glow of the street lamp. A tall figure, hunched, in a long raincoat.

Ralph opened the door.

His first impression was of a drowned weasel, so narrow-faced and sodden was the visitor. He was a pale man with long hands like claws which clutched his coat around his neck. The wet hair sticking to his face was so fair it was almost white. His light blue eyes stared at Ralph, unblinking, strangely reptilian. He did not speak and Ralph, baffled by the oddness of the man’s appearance and the irregular manner of his visit, found himself lost for words too. They faced each for a long few seconds until Ralph finally found his voice.

‘What is it?’ he said.

‘I have heard that you deal in beings of the supernatural kind,’ the visitor said. His lips barely moved when he spoke, so the words seemed to squeeze themselves out from between small pointed teeth. He had an accent, though Ralph could not place it.

‘Well,’ Ralph said, caught off-guard again. He usually had to cart his creations around for a while to flog them; he had never had a visiting customer before. ‘I do, yes,’ he said, before adding, for authenticity’s sake, ‘or, they seem to deal in me, anyway.’

The man glanced over his shoulder, down the darkened street.

‘I have something that may be of interest to you,’ he said. ‘Nearby.’

‘Ah,’ Ralph said. ‘I see.’

So this late caller wasn’t here to buy, but to sell. Ralph folded his arms, resisting the urge to scoff. As though anyone could cobble together a better freak than he could! He was the expert. It was like selling bacon to a butcher.

‘Look, it’s good of you to come by,’ he said, determined to get rid of the visitor and head home to bed, ‘but I only deal in real specialities, you know, truly occult creatures. For example,’ he added, unable to resist showing off, ‘I’ve just received an abnormality all the way from Paris. I’m working on preserving it right now. So…’

‘Sir, this is a true speciality,’ the man said. His eyes did not meet Ralph’s — rather, they seemed to drift, to float about the room. Ralph had to admit that it was impressive. The stranger was putting on a good show. But it was late, Ralph’s back ached, and he didn’t even want to see whatever soggy puppets might have been on offer. It would be humiliating, both of them standing there, pretending, knowing it was all fake — all just the work of needle and thread, of bindings and springs and painted scales.

‘Really,’ Ralph said, ‘I’m very busy. Goodnight-’ but as he went to close the door, the stranger’s hand shot out, quick as a striking snake, and he grasped the door frame. His coat fell away from his neck, revealing necklaces on which hung all kinds of charms and talismans. Some were feathers, some coloured stones, others looked carved from wood or bone. And as he moved, somehow seeming to fill the room, a gust of his scent billowed forward, and Ralph was struck by the smells of pine and leaf mould, of old coins, salt water and boughs heavy with rain.

‘You must listen to me. It is a true abnormality,’ the man said, and though he did not raise his voice, it boomed in the quiet of the workshop. ‘It is a thing like I have never seen or heard of before, sir, and I have travelled across this world too, further than France, to the earth’s darkest edges, and seen nothing, nothing, of its kind. It is not at all like that grotesque thing I see on your workbench there behind you, or any of the rags and sticks in the jars at the fairground. A beautiful creature it is, terrible too, but beautiful. I cannot put it into words, you must come and see, Ralph, see it with your own eyes. It is… it is a true wonder.’

Ralph stepped back, alarmed, afraid. ‘I don’t believe you,’ he said, but his mind was already wondering. He tried to picture something that could be both beautiful and terrible, something that was unlike any other creature in the world. He couldn’t do it. What would that look like? It was ridiculous, absurd. ‘No. I don’t believe you.’

‘You do,’ said the stranger, meeting Ralph’s eyes now. They were like clear pools, those eyes, pools in which small goldfish circled pits blacker than night. ‘You must. Come with me, it is nearby. Come now or someone else may find it first.’

‘I-’ Ralph found himself already pulling on his jacket, fumbling with his bootstraps. ‘I don’t usually-’

‘Come,’ the pale man insisted, and he flung himself back out into the night. Ralph stood for a moment, reeling, left behind. This was nonsense. He was being played for a fool, or the man was mad, or mistaken. He had seen a dog with mange or the slithering remains of a dead cat in an alley, and his mind had run away with him. That was all — an addled mind, a misconception, a child’s imagining.

But the door stood open, and the night air blew in the smell of rain. Ralph could hear the click of the pale man’s shoes fading as he hurried away along the street, and the workshop was suddenly the last place in the world that he wanted to be. An excitement bubbled in him that he hadn’t felt since he was a boy — a boy with his nose pressed against the glass of the skeleton exhibits at the museum; a boy who dreamed and imagined and stayed up all night poring over encyclopaedias of strange beasts from jungles far away and times long past. He felt like a dog called by a silver whistle, a pin dragged by a magnet. He felt delirious, as though he were dreaming, hazy and clear and wide awake all at once.

Ralph slammed the door behind him. The lamp winked out.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.