WALKING WATER

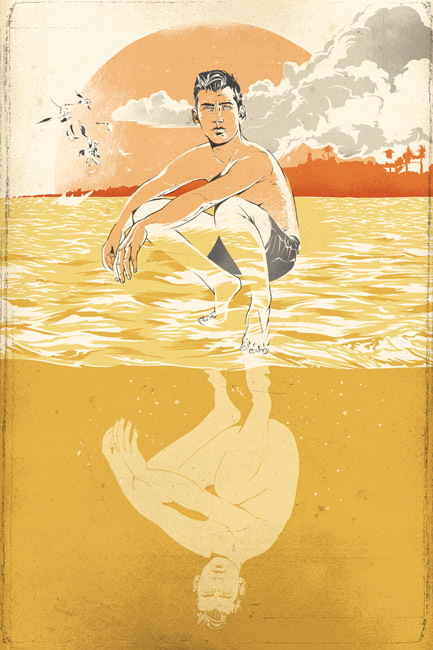

A day at the beach takes a surprising turn in Carol Farrelly’s short story of paralysis, courage and willpower. Illustration by Jörn Kaspuhl.

Calum watches the boy paddle amongst the froth of waves. He’s a disaster in the water, all skinny limbs and nerves. His legs splay like a newborn calf’s. He flaps his hands above the surf as though someone is dipping him in a foul, green medicine. Another child, Calum thinks, who does not live in his own skin. Someone else whom fate might have chosen instead of me.

Calum dog-ears the page on Plockton, leans back and presses his head into the scratchy, orange-striped deck chair. He closes his eyes. Twenty years since he stopped living in his own skin. Twenty years to the day — a day which now drifts pink-orange across the back of his eyelids. He casts his mind back to that very moment, as the boy he once was falls again in slow, balletic motion. White heels slide along tongues of pea-green seaweed. Legs spin up into the air. An airborne gymnast one moment, the hero in an action film the next; then Superman, but Superman losing his powers, pierced by a sliver of kryptonite. Jags of black rock bite once more into his ten-year-old spine. Snap. He crumples just like the actor who pretended to fly. Paralysis from the waist down. End of the show. Curtains. Lights. Feet crunching against scattered popcorn and crumpled tickets.

Now the faces clamour above him again, fuchsia blotches against the summer sky. His mother’s blue eyes stare down at him yet seem farther away than the sky. And Rob was there too: the first to reach him. His galloping feet sprayed coral sand across Calum’s arms and chest; his bubblegum breath cooled Calum’s cheek. He stared and did not laugh or tease, in that moment when Calum stopped feeling his legs.

Calum frowns. He cannot be sure of the memories. Stories that one’s grown-up self pastes together and tells the remembered child. Perhaps he only imagines these thoughts for his ten-year-old self. Maybe there were no visions of gymnasts or superheroes. No god’s-eye view. No jags of jet-black kryptonite. Rob might not have been the first to reach him. But the slow motion is true. He is certain of that slow swirling silence. The absence of sea and wind and children’s chatter. The sound of paralysis about to shudder into him. Nobody can make up a sound like that.

‘Maybe it’s time to go now, eh?’

He opens his eyes and stares up into Rob’s tanned face. ‘No thanks. Quite happy where I am.’

He looks towards the sea again for the wobbling, calf boy. He’s still out there, up to his waist in the water now and he moves as though he’s ploughing treacle.

‘Sure?’ Rob mumbles.

‘Positive.’

Rob disapproves of their return to the beach. The victim, he thinks, should never return to the scene of the crime. Last night, he tried to talk Calum out of it, like most folk would — the folk who think you should move on, adapt, celebrate the ‘just-glad-to-be-alive’ philosophy. Folk who wish you would just accept the inability to walk, run, jog, tiptoe, creep, saunter, hop, spin, waltz. Rub out all those words. Too many options, anyway. Even those who can, don’t. Accept with the same resigned spirit as they have accepted the receding helmet of hair, the middle-age paunch, the tone-deaf ear. And they’re right, of course. Never play the dying swan. Never consent to the eyes that turn away from you. The sudden hunt for a mobile phone that is not ringing. The third-person questions they vomit onto the nearest, likely chaperone.

Rob sighs and faces the water, hands on hips.

They both stare out at the matchstick boy. The waves are lapping against his ribcage, but still he stays upright, afraid to launch himself into the rolling waves.

‘Ironic, eh?’ Calum laughs.

‘What’s that?’ says Rob.

Calum nods towards the boy, a daub of frantic pink amongst the turquoise waves.

‘That he’s allowed his legs.’

‘What?’ Rob turns.

‘It’s a waste. I’m sitting here, coddled in cushions, my legs atrophied. Meanwhile, he’s got perfectly good legs and he’s afraid — afraid to use or enjoy them.’

Rob’s cheeks colour. He turns back towards the sea.

People don’t like it when you started cooking up self-pity. Never mind when you become vengeful, when you want to steal boys’ limbs just because you could use them better, just because they lack your gift for the water. And people are right again, of course. Rob’s right to be sickened, right to jog away from him now and head towards the water. Envy, however, is an instinct with him now — a simple bodily reaction, like goose pimples. The boy he used to be flutters before him sometimes, like a watercolour ghost. Swirls of sunbaked skin against churning, gymnastic water. And he rages at the loss of the sleek, amphibian body.

Rob, though, should understand. Rob knows what Calum lost that day. Two years they trained together, battering up and down the swimming pool lanes every school night, every weekend. Rob knows that Calum was an extraordinary swimmer. He must remember how he glided and surged and arched. A superboy in the water. It’s because he remembers, perhaps, that he says nothing; he drifts away now towards the fringes of coral shore, pretending to scour the demerara sand for shells. And that’s why twenty years ago, for those long eleven months, Rob did not once visit his hospital bed. Calum was a hard act not to follow.

Rob knows all that. He must hear that story now in the shell he lifts to his ear. Other men simply fail. They never become footballers or lead guitarists, never see their names in neon, never even strap a battered backpack around their shoulders. Not enough talent or perseverance. But Calum’s dream was pulled from under him. The world folded its arms and shook its bearded, sea-green head. You’ll never swim again. No Olympics. No applause slapping against wet, white tiles. A crumb of prehistoric rubble got in the way. Forget predetermination or rhyme and reason. Just snap. Snap went his backbone and his life. A parched strand of seaweed underfoot.

Rob places the shell he lifted back onto the beach.

Calum turn and stares again at the boy with the wasted legs. The sea has reached his chest now, but still he plants his stubborn feet upon the seabed, an astronaut visiting a world that does not like him. He won’t offer himself up to the water. He thinks walking the seabed is good enough, brave enough. And perhaps he has a point. The lapping of green water against your skin is enough. Sand and crushed shells pressing into the balls of your feet, fronds of seaweed licking at your hands. These are surely enough.

Calum’s gaze drifts. Rob still paces the sea’s edge. A pair of newly-weds or dirty-weekenders splash one another in the shallow waters. A family, comprised of Mum, Dad and a small red-headed girl, shake the water from their limbs and jog towards their deck chairs, already tasting their chicken sandwiches, fruit cake and lemonade. But the boy, their boy maybe, is suddenly nowhere. Gone. No sign on sea or land.

And then, he’s there. His blonde head bobs above the water. And then he’s gone. The water sucks him underneath. Calum begins to count. One, two, three…and the head reappears. Then under again. The boy can swim, after all. He is treading water. Calum shuts his eyes and drifts back again. The waves close above him. The warm waves, like cat’s tongues, purr against his scalp. His legs begin to float in the salt water. And he pushes himself up, up towards the sun and air and people; he opens his eyes.

The boy is still moving through the water, but his movements are too sudden. Each duck and rise is frantic. His arms flail against the water as though he’s inside a nightmare, fighting. The boy cannot swim; his legs are no use to him. He’s drowning.

Calum scans the beach. Nobody else notices. Rob is strolling farther along the shore; the couple are chasing each other through the water; the family are biting into their doorstep sandwiches. All are absorbed in their perfect day at the beach. Nobody but Calum sees that a boy is drowning.

‘The lad!’ he shouts towards the Mum and Dad. ‘He’s drowning!’

The smiling parents continue to rustle their foil-wrapped sandwiches. They do not hear.

‘Rob!’ he yells.

Rob is too far away; he does not turn.

The boy’s head bursts again through the water.

Calum closes his eyes. The water is lukewarm against his skin. His toes tickle a mane of pea-green seaweed, soft and feathered in the water — the beautiful, transforming water. It’s tempting to stay beneath in this forgiving, underwater cocoon. The immersion in a slower world, where the softer pull of gravity makes you glide and drift rather than tumble and crash and break. Kindness without white uniforms. Massages without paid hands. It is better, perhaps, to stay underwater.

His eyes flash open.

‘Face down,’ he whispers. ‘Trust the water. Breathe out. Push your palms against the water. Face down now. Trust the water…’

Calum imagines the boy’s arms rising through the air. He closes his eyes again. He sees his perfect legs paddle up and down, up and down, steering a course through the sand-misted water.

‘You’re flying, remember. You’re the next superhero. This moment, right now, you’re invincible. Enjoy it…’

Calum hears a clamour in the world above. Legs run; voices cry.

He opens his eyes. Rob is racing into the water. Ten years as a lifeguard. He knows what he’s doing. He’ll reach the boy and save him. Lifeguard saves young boy. Hero. Colossus. Superman. The red-top headlines already rustle in Calum’s hands. They might even describe the tragic accident Rob witnessed as a child, the accident that spurred him on to wear that invisible superhero cloak. And, in the closing lines, they’ll mention that the crushed boyhood friend, the paraplegic, witnessed the rescue and was ‘proud.’

‘Feel the water,’ he continues. ‘Don’t surrender. Trust yourself.’

The boy’s head emerges again. He’s nearer now to the shore. And then the head ducks. His movements are cleaner now. Up and down, push and pull, trusting — just as Calum instructed.

‘Good boy,’ he smiles, closing his eyes again.

He feels his arms surge through the water, pulling apart a glorious blue channel in the waves — a speed tunnel or ‘the aquatic wormhole’ as he called it as a boy. And he remembers again. There’s nothing like the touch of sun-golden water on your ten-year-old limbs. The feathered salt cleaning out your insides. The kindness of levitation. A halfway house between earth and moon. No raised voices or ambulances. No wheeled chairs or cushions. No school reunions or best man speeches. No past. No future. Just now. And that’s what he mourns most of all.

The boy careers out of the sea, refusing Rob’s arms. The mother rushes up to him. The father and little girl scramble after her. The mother drapes a plaid picnic rug around the boy’s shoulders, but he shrugs her off. His younger sister bounds in front of him, sideways, like a crab. She doesn’t say a word. She just stares as though she’s never seen him before, this boy who has just walked on water.

Rob slaps a wet hand on Calum’s shoulder.

‘Found his feet in the end, eh?’ Rob gasps. ‘Did it all on his own, eh?’

Calum nods.

As the boy draws close, Calum turns to look at him. His eyes are so blue they make him want to look up at the sky. The boy breaks into a grin and Calum smiles back as the last drops of water fall from the boy’s shins onto the dry, coral sand. The last soothing drops. Gone.

Calum pulls at his blanket and turns to Rob.

‘Let’s go,’ he says.

To ensure that you never miss a future issue of the print magazine, subscribe from just £24 for 4 issues.